The Agent 327 director retraces his seven-year journey to create his acclaimed new VFX short.

When Colin Levy came up with the idea for Skywatch, he was fresh out of school, and fresh from directing Sintel, the Blender Institute's 2010 open short. Today, he's a Pixar veteran – his resume includes work on Finding Dory and Inside Out, not to mention another spell at Blender Animation Studio, directing Agent 327: Operation Barbershop – and Skywatch has finally got its public release.

Set in all-too-plausible near future, the 10-minute VFX short tells the story of two tech-savvy teenagers (13 Reasons Why's Uriah Shelton and Steven Universe's Zach Callison), who hack into what seems to be an Amazon-style home-delivery drone system, only to find themselves entangled in a lethal conspiracy.

The sleek visual effects for the movie were created primarily in Blender, with the help of a $50,000 Kickstarter campaign and around 50 volunteer artists, including several well-known members of the Blender community. Today, Skywatch has racked up over 450,000 views (and counting) in its first two weeks on YouTube, and Colin is in talks to turn the proof-of-concept short into a full-length project.

We caught up with Colin between pitch meetings to retrace Skywatch's seven-year history, to explore how Blender was used to create the visuals – and to ask him why it took him so long to finish.

What were you doing before Skywatch?

Sintel got released in 2010. It did very well online, and it opened up questions in Hollywood-land about whether it could be adapted into a feature. Those were questions that I was utterly unprepared for. But I got my first representation there: I got an agent and a manager out of the success of Sintel.

It was a big decision what to do next. I'd dropped out of school to do Sintel, so I decided to go back and finish my degree. I moved back to Savannah, Georgia and did my senior year [at SCAD]and my senior film, which was a short called The Secret Number, a psychological thriller.

By the time I graduated, I had applied to Pixar, so right after school, I moved to California and joined the studio as a resident in September 2011.

So you were working at Pixar when the idea for Skywatch came up?

That's correct. I was finishing up my senior film for the first six months of my time there, then the following year, for the first time in a long while, I didn't have a personal project to work on. That void needed to be filled, so in 2012, I started brainstorming.

I was working pretty crazy hours, so my weekends were spent on life-maintenance errands: doing my laundry and going to the grocery. I found myself staring at my empty fridge one day, and thought: 'Why don't we live in a world where fridges restock themselves?' That was the origin [of Skywatch]: what would be the most seamless implementation of drone delivery look like?

And this was before Amazon started setting up a drone delivery network

It was. It seems crazy how the world has caught up. The very first doodles for Skywatch were more of a Brazil-type world of chutes and conveyor belts and pneumatic tubes, then the idea of delivery drones came along later, but it's been fascinating to watch [Amazon's] efforts.

Planning for Skywatch: the entire movie laid out on note cards.

When did you shoot the film?

It was right after I wrapped on Inside Out. I took a leave of absence in the summer of 2014, and at the end of that three-month window, we shot principal photography.

It wasn't the last time we would do a shoot: we ended up doing a few different pick-ups, then we shot the commercial [that opens the short]another year, then the Jude Law cameo was separate, so it was kind of piecemeal. But after that leave of absence, I came back to work, and Skywatch became my passion project that I did at nights and weekends for a couple of years.

How were you funding things at that stage?

We were really lucky. We were planning to do it for next to nothing, self-financing along the lines of The Secret Number, and my previous film, En Route, where we made a very ambitious live-action film for $3,000. We were planning on calling in a bunch of favours.

But for the first time in my life, we were lucky enough to get a financier interested. We got an executive producer who had reached out a year prior. He had a feature screenplay he was interested in having me direct, but at some point, we started talking about the short film as an alternative project for him to get involved with. Throughout this extremely lengthy process, he’s been incredibly supportive and a true champion of the vision for Skywatch.

That funding got us through principal photography, but it's amazing how expensive that is, so [the money]just disappeared. We had no budget for post-production. I was editing for a year and half.

Why did it take so long?

There's quite a bit of post-viz. We don't have live-action photography of drones so to even figure out what the cut should be, I needed to do versions of shots with temporary rigs and OpenGL renders.

In 2014, I screened the film at Pixar and got some notes on it from colleagues. It was good feedback, but really brutal, so a year and a half after [principal photography], we got the kids back to do some pick-up shots. I rewrote part of the opening, and we cut a scene on the roof, all to keep tension up.

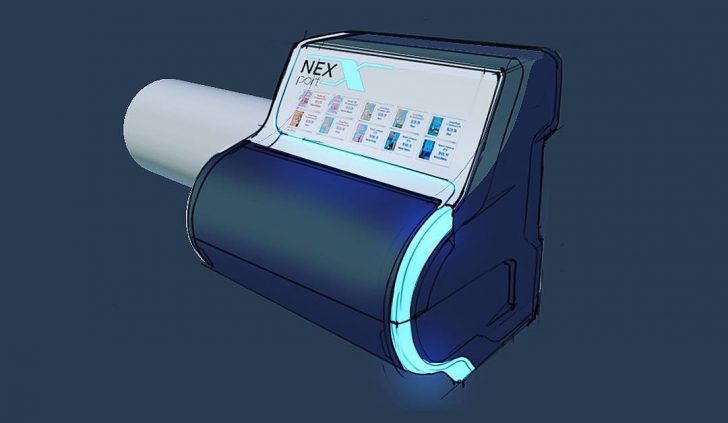

Concept art of Skywatch's NexPort portal system, created by Matt Bell.

Concept art of Skywatch's NexPort portal system, created by Matt Bell.

Had you started the final asset build by then?

I think we'd started modeling, and probably shading and rigging. Certainly the designs were well underway. Matt Bell was lead designer of the NexPort technology and the drones. He's phenomenal.

Why did you decide to use Blender?

The artists I've gotten for my previous live-action projects have not been Blender users. En Route is a great example: the team consisted of people from school, and they were being taught Maya.

For Skywatch, I wanted to do things differently. Because of my comfort level with Blender, I thought it would make sense to use a tool that I know and love. But it was also partially because of the community, knowing how much volunteer work there would be.

More Matt Bell concept art, this time of a drone from the movie.

Who came on board first in the VFX team?

Sandro Blattner, my VFX supervisor, is someone I went to school with, so he had worked on En Route. We had a great experience on that project, and we'd been tracking one another's careers since then. It felt like Skywatch was going to help us both get to where we wanted to go.

Andrew Price also came on board early on. I pitched him an idea by email. Neither of us had any idea what this was going to become, that this would take six full years, but he was into it.

How did you recruit 3D artists?

There were two scenarios. Andrew put out an open call. Because of his visibility in the community, we got quite a lot of submissions we could go through. From there, we put together a small team of folks who could start implementing some of the design work we'd done in 3D. Both Paweł Somogyi, our 3D lead, and Jonas Prunskus and Anderson Baptista, who did a lot of early work on the assets, came from that group.

Because I've worked on projects at the Blender Animation Studio, I was also able to reach out to people I've worked with in the past. Nathan Vegdahl is a great example. He and I worked together on Sintel, so I knew he was one of very few people who could do the drone rig right.

Nathan Dillow and Hjalti Hjálmarsson – who were together responsible for the vast majority of character animation for Agent 327 – did some of the more exciting drone shots, like the transformation sequence with the guns popping out.

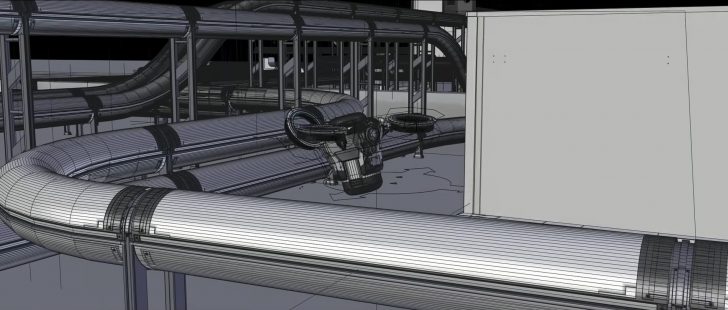

The drone as a 3D asset, opening up during the transformation sequence.

The drone as a 3D asset, opening up during the transformation sequence.

How far did the $50,000 you raised on Kickstarter stretch in post-production?

A lot of it ended up going to vendors we needed to hire for specific things, like roto. No one wants to do roto, and we had a lot of it. We had to focus the money on tasks that no one wants to volunteer for. Certain tools and online services took a portion of our budget, including Dropbox and RenderStreet, a Blender-friendly render farm we used to render the majority of the film. We also worked with a studio in Austin, Texas, Mighty Coconut, which was really exciting, but because they were a vendor, another chunk of that $50k went to them.

That's why I'm so indebted to the many volunteers who found it worth their time to chip away on a lot of little tasks. Some people just did one thing: they worked on an asset for a weekend, or animated one shot. Others, like Paweł, stuck on from beginning to end. He was game to do anything and everything, and was an absolute joy to work with.

Paweł is based in Poland. How did you collaborate?

We were mainly working via email. I'd do quite a lot of video critique: he'd send something over, and I'd do a screen capture while I was giving my feedback on the next iteration. There wasn't much face-to-face contact. It wasn't until the Blender Conference in 2017 that I met him in person.

He and Jonas and I hung out and I treated them to a steak dinner. I can't possibly thank them enough, but it was really great to at least have that moment together and connect as human beings.

How easy was it to manage input from the Blender community?

When you're working with volunteers, your project is not necessarily a priority in their lives. You can't fault anyone: if they work on your project for five hours, they're helping you for free. But it's a challenge to keep people interested. We spent a lot of time getting people up to speed, then after a month or two of not hearing much back, we'd get an email saying, 'I'm sorry, I don't have time for this.' That's happened with every project I've worked on, and it's what makes guys like Paweł such magical unicorns.

The official VFX breakdown for Skywatch, showing how some of the key CG shots were created.

What was Blender used for on the short?

Pretty much all of the CG. The drones, the portals, and a lot of the set extensions are done in Blender. We also did quite a few entirely CG shots on the roof, like the transformation sequence, and the lingerie box falling out of the pod. All of the turntables on the computer UI are done in Blender too.

The only thing we didn't use Blender for is compositing. The whole thing was composited in Nuke. We rendered out AOVs for everything, exporting multi-layer EXRs, then compiled a beauty render back in Nuke so we could push and pull everything around.

What about simulation?

There were a couple of smoke sims that were done in Houdini, and shipping drones' rotor exhausts are a Nuke particle sim. But I did quite a few simulations in Blender. The cargo drones' rotor exhausts are done in Blender, and the gravel in the shot where a cargo drone comes and scoops up [one of the kids]was a Blender physics sim. It brought my machine to its knees!

A full CG shot on the rooftop towards the end of the short, showing the range of assets created in Blender.

A full CG shot on the rooftop towards the end of the short, showing the range of assets created in Blender.

Was there anything else that Blender wasn't used for?

There's some stuff that would normally have been done in Blender that Nuke could handle, like set extensions with camera projection. And a visual effects vendor came in at the end to do the shot at the end when the kid jumps in the truck, so they used their own tools for that.

I'd say that Blender was used for 95% of the CG. There are between 100 and 150 shots with pretty hardcore Blender work.

How did Blender hold up in production?

It was extremely capable in every respect. Cycles felt like a risk when we were first talking about it in 2013, but now it's so mature. We've been thrilled by how far we've been able to push the visuals and come out with striking, very physical-looking images.

What was the hardest thing to do with Blender?

The asset library system was a bit of a pain. We have a sky full of drones on some shots, and they couldn't be the same asset, even though we would have liked them to be. If we had a rig update, we had to roll it out across all of the drones [individually], because you couldn't link a rig into multiple animation blocks. Of course, we did all of this pre-Blender 2.8, so the toolset is a lot stronger now.

Art directing physics simulations is also extremely tricky in Blender – sometimes it feels like you’re sorta stuck with what you get. And building a system to do repetitive sims across a whole bunch of shots (like rotor exhaust) proved to be too labor-intensive to do in Blender. Lastly, we initially tried to design the drone’s eyeball animation in 3D, with its interior lenses and blinky lights, but it ended up falling to comp. A lot of this came down to choosing the right tool for the job.

Colin discusses how Skywatch was created at last year's Blender Conference.

How much time do you think you spent on Skywatch in total?

I don't even want to know the answer to that. At Pixar, a single minute of animation takes well over a hundred 'man weeks' of work, and I think Skywatch is probably not far behind – although obviously with far fewer people working full-time, stretched out over six years. This has truly been my passion in life, but I hope never to work on another project for as long as I've worked on Skywatch.

So what's next?

It's been very exciting. I've been pitching my heart out. I've just taken 13 meetings [in a week]with creative development people at various production companies. They've all seen the short, they like it, and a lot of interesting conversations are happening about what the next iteration should be. Most of the interest seems primarily for a series rather than a feature.

Has the success of Skywatch online helped there?

We started setting up these types of meetings in November, and the reactions were fairly lukewarm. The online release changed everything. I don't know exactly why: maybe because of the reaction in the comments, or the coverage on Short of the Week or Slashfilm. People started sharing it in Hollywood. Conversations started. I have no idea why or how: [the process]is opaque to me. But cross your fingers for us: anything could happen at any time, but there is definitely significant, concrete interest.

And if there is a Skywatch 2.0, do you get to use Blender again?

That's a great question. We've talked a little bit about it, and each scenario is probably a bit different. The budget for TV is lower than for a feature, and the development time would probably also be significantly lower. We've already built all of these assets, and they would probably function well enough in the next iteration. I think it's possible that we could make use all of this work we've put in, and I would love to keep collaborating with some of the folks we've worked with.

2 Comments

Congrats, Colin, and everybody else who worked so hard on Skywatch! Happy Holidays!

Thanks so much for this wonderful article, Jim! An honor :) and happy holidays!